C. Thi Nguyen - 'The Score: How to Stop Playing Somebody Else's Game'

A valuable but vexing book on games in relation to philosophy.

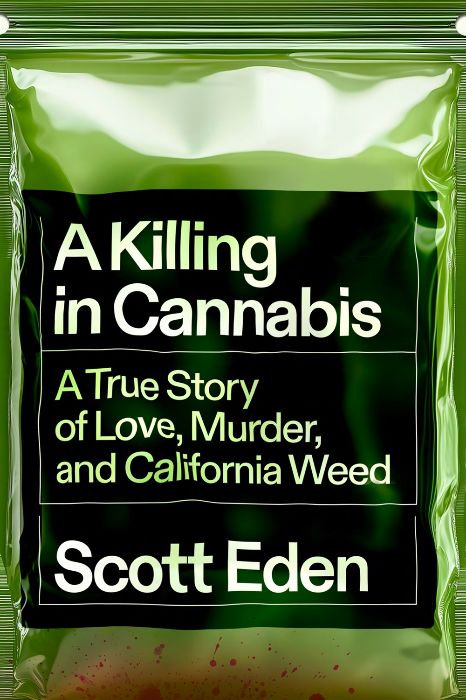

This book starts strongly. I usually don’t read true-crime books that start like novels. When most versions of this type of book kicks off trying to be a mixture of Arthur Conan Doyle’s books on Sherlock Holmes and a Netflix documentary that shits over victims, things turn dour and boring.

Tushar Atre had big ambitions. He didn’t just want to take this outlawry into the light. He wanted his company to extract oil from a thousand pounds of biomass per day, which would have made Cruz Science one of the largest cannabis manufacturers in California and thus the world. He’d promised as much to his investors, a venture capital outfit specializing in cannabis start-ups, which had injected $4.25 million in a Series A round into Cruz Science earlier in 2019.

Scott Eden, the author, wants to teach the reader how modern-day North American cannabis business works; the knowledge is quite necessary to understand the motives behind what happens in this book on several levels: there’s the illegal history of cannabis, the history of how it became legal in most of the USA, and how there’s a lot more money to be made by handling cannabis through illegal means than through legal ones.

To begin with, a startup is a small company that aims to go big. It’s not got the wheels, the money, nor the possibilities like a big company. A startup can move a lot faster than an old-school company, one with more people, more wills.

On the other hand, a startup can generate a lot of money quickly, which can be a much harder problem to handle than just peeling through hundreds of employees. For example, your investors could make much different demands than if you’d not have a lot of money.

In the world of cannabis, to develop and create means to get permits. It’s a lot cheaper, a lot less time-consuming, and a lot faster to produce certain things illegally than through the sanction of the government.

Into this world stepped Tushar Atre, the main person in this book. The next quote contains information from the start of the book, so it’s not a spoiler; actually, reading the back of this book would provide more ‘spoilers’ than this review does.

Investigators had been busy in the hours after Atre’s kidnapping.

They learned that Atre had had not one, not two, but three disgruntled former partners in Cruz Science.

The start of the book drew me in. There were fragments that read like a Walter Mosley novel: a crime’s been committed, but the story isn’t bang on into the action. Short sentences.

Atre’s life is dissected throughout the book, where the rhythm is Atre/cannabis business/threats/romance/crime. At first, this felt good.

Indeed, crack was to cocaine as these cannabis extracts, called dabs, were to the dried buds that got rolled into joints or pushed into bowls. A closer analogy was a hashish water pipe, à la Alice in Wonderland’s slow-talking Caterpillar taking puffs while lounging on the mushroom: A dab rig was like a space-age hookah. A few hits from the rig, with its small lump of blondish concentrate heated by the torch to more than five hundred degrees Fahrenheit, could induce a special kind of catatonia, ambushing the smoker’s brain until he was falling into the cushions of his couch, sucked down into the pillows and springs and deeper davenport structures as if by some psychotropic gravity. Couch lock was the term stoners used for this condition. In the early 2010s, prices for such extracts had reached disorienting heights: Thirtyfive thousand dollars a kilo wholesale in some places. In Santa Cruz there were extractor kids who were millionaires without bank accounts. Talk about theft risk. The smarter ones knew they had to do something with all that freaking cash!

There is much information to be gleaned on how to make cannabis in this book. Far too much information, I think, to make sense. At times, I felt like I was studying for a How to Make Cannabis 101 course; where was the true-crime sense of excitement that the first ten per cent of the book made me feel?

There’s funny yet drab stories about Atre, a man who seems to have been charismatic, talkative, persuasive, and reckless.

Then Tushar revealed the secret; it wouldn’t have been sporting not to: Do not look at the animal, he said. That was the trick. Do not make eye contact with the animal. If you don’t, the otter will allow you to come right up to it—watch me—and then Tushar made his move, looking off but paddling right up to one of the cute marine ferrets lolling in the sun, and he did it—he squeezed one if its weirdly squishy paws. Tushar’s face for an instant carried the look of victory, and then the otter lunged and snapped and sank its fangs into his hand. Back on land, a doctor wrote him a script. The bite wound was infected.

There are a few different threads to keep track of during the book, threads where different entities and individuals are pointed to as Atre’s enemies and plausible suspects throughout this story. The plot is extremely straight-forward and sadly, therein lies the crux with the book: it’s plain but too long. If this book had been turned into 50 or 100 pages, it would likely have been far improved. On the other hand, the start of the book is so powerful it makes the rest feel like a meandering, hapless chore to read.

Sadly, this book started out finely and then quickly descended into a lull of sorts, one where a green author is keen to impress by trying to make something happen by really making nothing happen: so, I’ve learned a lot about the cannabis trade; how does this improve the book? I nearly expected an exam at the end. Instead, I’m not left with the innards of Atre through his family or friends, not really. Sure, it’s one thing to insinuate he was a mystic, or at least a confused person who tried to fit the bill of a commonplace tech-cum-drug entrepreneur who got mixed up with people whom he tried to fool. If only the sociological and humanistic parts of the book had been kicked into gear. If only the rhythm and melody of the start of this book had made good on its initial promises. If only.