Scott Eden - 'A Killing in Cannabis'

A book that should have been trimmed down and kept as exciting as its start, is not.

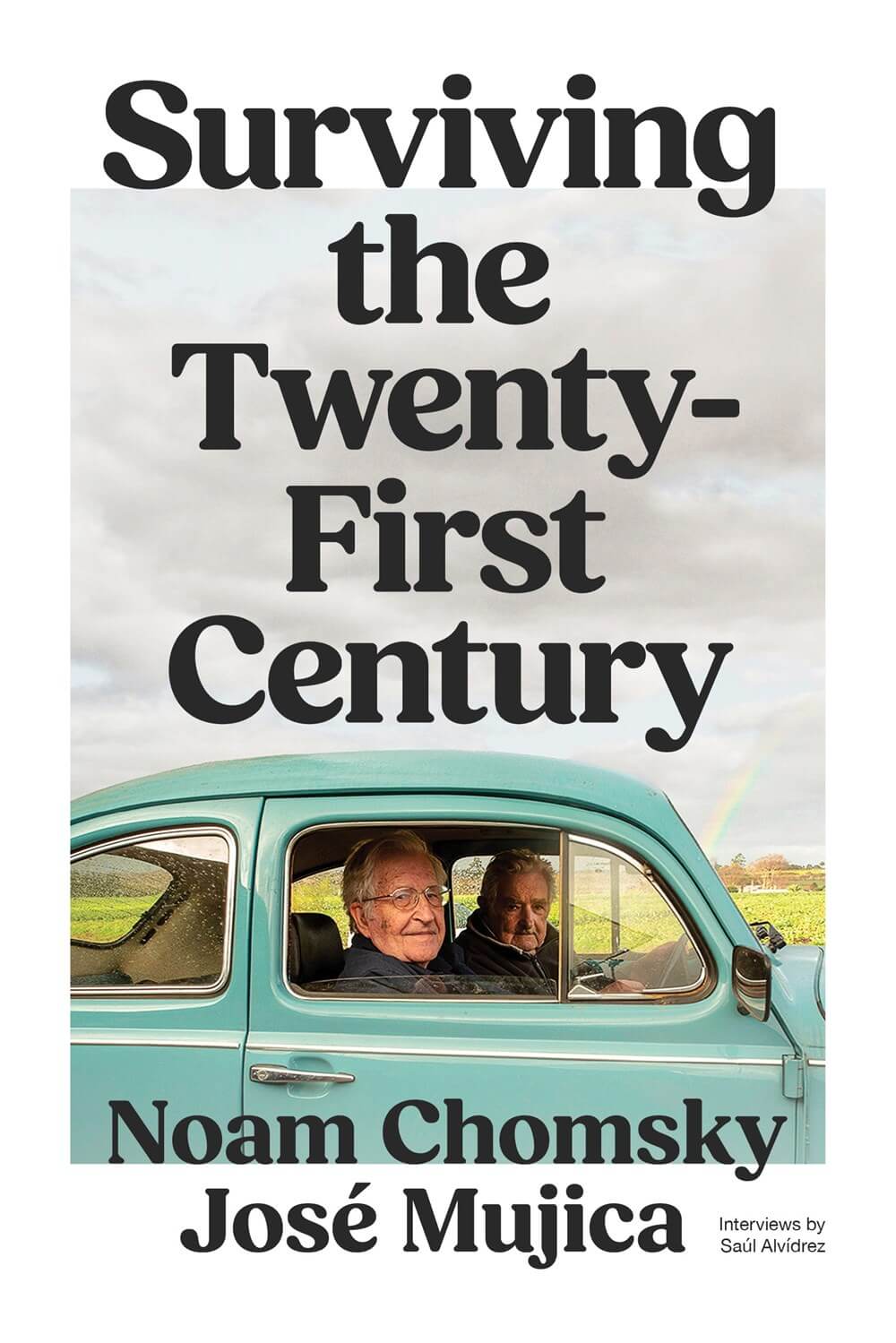

Saúl Alvídrez is a fiery person who’s for years been making a documentary. The documentary is about when Noam Chomsky and José Mujica met in the year 2017.

If you’ve not heard about these two persons before reading this line, please stop reading this article and first check out their Wikipedia articles.

Alvídrez has recently had this book published, before the documentary is released. The book is an astounding piece of work, something of a monument. It’s filled with compassion, empathy, and love. From the introduction:

Chomsky has an extraordinary mind, but in conversation he is kind and warm and speaks simply. In his office there were piles of books everywhere, a small Mexican Zapatista doll (surely a gift from EZLN, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, which Chomsky has long supported), and a large photograph of philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell accompanied by a quote from Russell: “Three passions, simple but overwhelmingly strong, have governed my life: the longing for love, the search for knowledge, and unbearable pity for the suffering of mankind.”

Before digging into the humanistic and political parts of the book, I’d like to run a quote that points to how different this book is to a lot of other ones that involve Chomsky, even when this one involves Mujica just as much.

Saúl Alvídrez: Pepe, what is love?

José Mujica: Love? At my age it is my habits and solace. Love has ages. It is volcanic when we are young, and at my age it’s sweet habits. Getting used to everyday things that seem unimportant but that in the end are the only important ones.

Saúl Alvídrez: Professor Chomsky, how do you define love? Noam Chomsky: Love is timeless. If we go back to Homer, the Greeks went to war because Helen was abducted. Penelope then wove for ten years as a way of delaying her suitors as she waited for Odysseus to return. Sometimes you can be waiting without knowing you are waiting. I waited for many years before I met my wife, Valeria, and I have discovered a new kind of love.

Saúl Alvídrez: You and Valeria have been together since 2014?

Valeria Wasserman Chomsky: Since 2013.

Noam Chomsky: It proves you can find love at eighty-seven.

Valeria Wasserman Chomsky: You were eighty-four!

Lucía Topolansky: We have a friend, an anthropologist, who found love at ninety-four, and he wrote me an email saying, “Spring is here!”

José Mujica: That is incredible. Daniel Vidart is his name. He has a new book out every two months, or so it seems.

Lucía Topolansky: Vidart told us that when he was young, he made plans for several years at a time. Then he got older and planned for months. Now he plans for a single day.

Noam Chomsky: For me it was different. I had contemplated that my life would one day end, but now that I have found love I hope to live forever.

You won’t find that in any other Chomsky book, not as far as I’m aware, anyway.

I like Mujica’s self-introduction.

My name is José Mujica. Like many with the name José, Pepe is my nickname. My father’s family is from a little corner of the Basque Country. My mother’s family were Italian peasants, from Liguria, which is in northwestern Italy. I was born in a neighborhood full of ranches, a little way from the city but some distance from the countryside. I love the land. I am also a peasant. I feel close to the earth and love nature. I cultivate philosophical sobriety, and I’m a kind of neo-stoic. I am a very lucky guy. Death has been around me many times, but it didn’t want to take me. I have been given time. When I was young, I had the defects of all young people. I fell in love a few times. I wanted to change the world. I became a militant and went to prison. Our movement decided to change after the end of the dictatorship. We turned to legal militancy, we began to move forward, we accepted the rules of liberal democracy. I was deputy, then senator, minister, president, and now I am saying goodbye to politics.

Chomsky quickly digs into what differs some South American countries from western, so-called ‘non-primitive societies’.

Ecuador, with its large indigenous population, sought aid from the rich European countries to allow it to keep some of its oil reserves underground, where they should remain. The request for aid was refused. Ecuador revised its constitution in 2008 to include “rights of nature” as having “intrinsic worth.” Bolivia, with an indigenous majority, passed the Law of Mother Earth, granting nature rights equal to humans. In general, indigenous populations are well in the lead in seeking to preserve the planet. The countries that have driven indigenous populations to extinction or extreme marginalization are racing toward destruction.

Perhaps that’s something else we should think about.

One of the main themes throughout the interviews in this book is how Alvídrez speaks for young people: what can we do to fix Crisis X? The answer boils down to collaboration.

José Mujica: I think that in the coming decades the world is going to be thrown into turmoil in terms of how work is organized and the distribution of income. The technological revolution is advancing too quickly, and society cannot keep up with the changes. A cataclysmic time is coming. The automation revolution is upon us, but wage distribution proportional to that increase in productivity is lagging, and that is going to create fraught conditions. The left must fight for civilization, for these things that we are discussing in terms of public policy. But not everything is poetic and not everything is catastrophic; it will depend on how the organized will of the masses develops.

For me, it’s beautiful to see two wise persons speak about culture and what’s happening with humanity.

José Mujica: My generation made a naïve error. We believed that social change was only a matter of challenging modes of production and distribution in society. We did not understand the immense role of culture. Capitalism is a culture, and we must respond to and resist capitalism with a different culture. Another way to put this: we are in a struggle between a culture of solidarity and a culture of selfishness.

Noam Chomsky: Well, it’s quite interesting to see how culture develops. If you look at some of the greatest cultural contributions of the modern period, you’ll see that they originated in some of the most horrible conditions that have ever existed. Think of the brutal repression of African Americans in the South, which gave us blues and jazz. The left should focus on creating the conditions in which natural human instincts can develop and flourish. Marx wrote of liberating workers from their “animal functions” so they could focus on their human problems without the impediments, barriers and restrictions imposed by the various repressive societies, including capitalist society. Remove those chains and let people be free to explore their own natural instincts and capacities.

José Mujica: True, but in this case, I am not thinking of culture that is sold, like professional music or dance. All that is important, of course, but when I speak of culture I am referring to human relations, to the set of ideas that govern our relationships without us realizing it. It is a set of unspoken values that determine the way in which millions of anonymous people around the world relate to each other.

How about some more beauty:

Saúl Alvídrez: Pepe, what gives life meaning?

José Mujica: It seems to me that a difference between humans and other animals is that humans can impart meaning and direction to their lives. And that is one opportunity we have: to push our lives in a certain direction. If we don’t give ourselves a direction, our lives will be managed by the market, and this poses a real dilemma. We cannot wait for a better world. We must fight for a better world and believe that a better world is possible. But each one of us has a better world to build within himself. You must be the master of your own life, not let it be managed from outside. For this it is not necessary to come to power or to change property relations or anything like that. It is necessary to fight inside our own heads. This is the strongest message we can transmit to young people: If you cannot change the world, you can change yourself. Do not let yourself be dominated. Why? The greatest miracle of all is that there is life. When I was younger, I was a humanist, and it seemed to me that human life was at the center. But now that I am older, I am less a humanist. I love the entirety of life on earth: the life of a little grass, the life of an ant, the life of a cockroach . . . Life is what separates us from the inert. We belong to that world. It is a classic philosophical question: What is the meaning of life? Shall we watch the world progress and just let things happen, or will we try to influence the shape of the world to come and attempt to increase human happiness? And one day when you are old you must look at yourself in the mirror and ask, How have I spent my life? Have I betrayed my goals? That is, have I spent my life paying bills, believing that progress means being hooked into a consumerist society that makes me a target for marketing? Or do I own the direction of my life? You may not be able to change the world, but you can learn to walk in the world without being carried along by the current.

There’s something very profound in what Mujica said. One more comment from Mujica:

Saúl Alvídrez: On the subject of young people, suicide and depression are crises facing my generation. The statistics are alarming. Many live with chronic anxiety. What can we do?

José Mujica: All living things are programmed to want to live. We are no different from other animals in this regard. Humans are privileged to have consciousness. We try to live, and we should be aware that the greatest miracle is our existence. To be born is to come from the world of nothingness and know that we are going to the world of nothingness. We must realize that this little bit of life is the real adventure . . . to know that, despite all the pains that this experience may mean. There is no greater good than the adventure of living. But we are social animals. If people have failures or difficulties, they can feel defeated, but there is no definitive triumph in life. Do you know what the only triumph in life is? Getting up and going back to begin again every time one falls. That is to say, the great prize is your way of life. Perhaps this is why nature programs us to try to live and, when we fail, people sometimes end their lives. There is a disease that gets inside us and is more and more present in society today. Why? Because you must be competitive, because you must succeed, because you must accumulate . . . In the end you will reach the same place where we all arrive: death. And that madness, which can be accompanied by a tremendous loneliness in the crowd, sometimes leads people to choose death over life. I spent seven years in prison without being able to read a book, and the night they threw me a mattress to sleep on, a mattress on the floor, I was happy. I even saved some crumbs for the rats that came at one or two o’clock in the morning. I had rationed the crumbs. The rats came, and I gave them a few crumbs. I learned that even the smallest animals scream in solitude, but I didn’t die. I followed the path of my life. We cannot be so weak as to give up the adventure of living. As I say, the true adventure, the true miracle, is to have been born at all. It is essential to have a cause to live for. Only with a cause in mind will you be able to get back up when you fall. I am not saying that we all must have the same cause. Some of us crazy people dream of changing the society in which we live, but having a cause can mean a scientific passion, painting, fishing, playing soccer, lying on your belly in the sun or whatever, but you must have a passion. In everything else we come already programmed—biology determines almost everything—and on top of that we have the brutal civilizing pressure of the societies we have created. But unlike the other animals, we can in some sense twist the course of our lives, and that is true freedom. You can take a decision for the direction of your life—something perhaps in opposition to what others want to impose—and choose how you are going to spend your life. In general, I believe that people who commit suicide suffer from deep frustration and believe that the world ends there, but in the world, you learn much more from defeat than from triumph. You don’t have to let defeat destroy you, but this depends on you.

Chomsky and Mujica don’t waste words.

José Mujica: Capitalism has been separating us, and we have to find new ways to build community.

Noam Chomsky: And all this can be done in urban communities as well. I think it’s entirely possible.

Where hope reigns over despair, you’ll find thought; hope rarely goes away in most aspects of life, and talk about how these persons spark hope in the face of oppression…

José Mujica: I have started to study Athenian democracy again. Aristotle was subversive. He defines a citizen as having the capability and right to participate in governing. Athenian democracy was by lot, and if you were chosen in the lottery, you had to participate. Any citizen could face you in the assembly and criticize you. You also could be a judge. Imagine: Socrates was condemned by a popular jury, chosen by lot. We have never seen anything like this in our own time. And yes, I know that the Greeks had slaves at this time, but according to Xenophon nowhere did they treat slaves so well. And there were slaves all over the world, but there was no democracy anywhere else—nobody dared. In the sixth century BCE in Athens, they were on the verge of a civil war because of the number of debt slaves, because at the time if you contracted a debt and could not pay it, you went into slavery. Then Solon was elected, who was a poet in addition to being a lawmaker, who decided to give freedom to the debt slaves and abolish all debts. The slaves asked Solon to compensate them for what they had lost by being slaves, but that was more than the aristocrats whose slaves had been taken away could bear. And what happened? Solon gave them nothing material, but you know what he did give them? He gave them the right to speak in the assembly and the right to vote. Do you see? He began to give them political power. That’s where democracy was born! Democracy was born in a desperate cry against inequality. And yes, of course, I know, Athens was a small society, of barely two hundred thousand people, but look at this: seven thousand people made up the government apparatus of Athens, and they rotated. They were drawn by lot and they all answered to the assembly. There were forty elected to oversee military matters and the treasury. You had to wealthy to be elected to the treasury, because if there was an embezzlement you had to be able to cover it with your own wealth. Have you ever seen anything like it?

This book is intense. It’s a labour of love. At times, Chomsky sounds pretty much like he’s done for the past decade, repeating what he usually has said about the dangers of climate catastrophe and nuclear annihilation of humanity; don’t get me wrong, I agree with him: those are likely the biggest current threats to human life. On the other hand, this is a very small grudge to carry in comparison with what this book brings. Buy it. It’s worth it. The documentary is coming!

I think the following beautiful and short paragraph from the start of this book should end the review:

I will conclude with two quotations, perhaps the most valuable ideas I’ve taken from Noam Chomsky and José Mujica. From Chomsky, “Think for yourself.” From Mujica, “Real triumph is getting up every time you fall and starting again.”