Scott Eden - 'A Killing in Cannabis'

A book that should have been trimmed down and kept as exciting as its start, is not.

A long time ago, yours truly was walking around the south of Stockholm city, Sweden. A few beers later, I felt well and alive, pep in my step. I was gonna meet some friends.

I happened to walk by Skivfönstret, a record store where something was going on. A lot of people were standing in a line and carrying records and trinkets. I had no idea what whas going on in the store. Most of the queuers were very well-dressed. Right there and then, a bouncer-looking guy told everyone to line up and I got pushed in line. Turns out I was pushed to the very front of the queue, much to the chagrin of the people who were supposed to be at the very front. Suddenly I was ushered into the shop and stood face-to-face with a sat-down Kevin Rowland.

I’d heard Dexys Midnight Runners. Strangely, a dear friend was very much into one of their masterpieces, Too-Rye-Ay1, and by osmosis, I was obsessed.

At this point in time, as I met Kevin Rowland, I stood a drunk wreck in front of a seemingly composed gentleman. I grabbed two copies of the CD version of Too-Rye-Ay from a shelf and asked Rowland to sign one for me and one for a friend. I can’t go into detail of what I asked Rowland next but it’s safe to say some persons of his stature would have found it either offensive, ludicrous, or funny; thankfully, I think he saw through me and laughed it all off. A gentleman, he was.

Fast forward to today.

As I read this book, Rowland’s memoir, I’m struck by a few different things. First, of our paternal relationship. The book makes it glaringly obvious that Rowland, as with many boys who were born in the 20th century, wanted his father’s attention and approval but rarely got anything but disdain.

‘What do you think I’ll be, Dad?’

He paused for a few moments, became suddenly very serious, and said, ‘You’ll be married with a kid when you’re 17.’

I didn’t say anything. I pretended not to know what he meant - but I did know (my brother Pat had already told me how babies are made). In those days, the early sixties, when a girl got pregnant, the boy married her. Plus, Dad had a younger brother, Paddy, who had got married at 16 under those circumstances.

Was I bad, weak? What was different about me compared to the others? There must be something wrong with me. I felt he could see right into me.

Dad’s outlook was the one that dominated our household. He was very strict and he perceived stuff like Elvis lyrics to be over-sentimental.

To be clear, Dad did think music and singing were things to be enjoyed, but only in their place - like on birthdays, or later when we had a car and would go on a holiday. Music was not to be confused with work.

That was serious. From the youngest age, my dad told me that my interests in music and clothes were wrong.

This book isn’t some rock’n’roll story of how a kid with a disapproving father rebels, eventually finds his own tribe and becomes a pop singer. This is a story of someone who took what his dad said very seriously, believed it and internalised it, so that it became his reality.

The book is written by a soulful and truthful person. To me, the language of a person who’s been through rehab shines through the pages; Rowland is sober since decades back, and has always been a soulful person. I mean, just read the lyrics for the Dexys song ‘Reminisce, Pt. 1’2 and you can quickly tell that he’s someone who wears his heart on his sleeve: his Irish heritage and soulful music and writing.

Having said that, Rowland not only let his lyrics do the work but the music, too.

Dexys turned famous all over the world for ‘Come On Eileen’, but that song is such a little speck of all that is Dexys, soulful and experimental as that song is, mixing Irish and pop-music elements. To make things clear, Rowland emphasises throughout the book that Dexys is, and has always been, a team effort, a project of sorts where the result is greater than the sum of its parts. Dexys really are something. From creating different clothing styles over the years to carefully (and sometimes wastefully) making music, this book lays it all out.

I’m glad to say Rowland constantly—as most human beings do in speech—returns to describing his family life throughout the book. The book is a fairly chronological journey from his first to his later years and one thing that Rowland’s addiction and journey since has resulted in, is how honest he seems. Gracefully, there’s very little here in the sense of shame. I mean, Rowland’s father shamed him enough, which makes it even more astonishing that he’s not perpetrated shame. Still, this is a book, and the book is written by a very clever storyteller.

I discovered wanking at the age of 14. The first time it came about, I was off school, with the flu. I was lying in bed reading one of my sister’s comics. There was an artist’s illustration of a girl about my age. I looked at her as I held my cock. It felt pleasant, so I continued. I don’t remember exactly how it happened. But I started to enjoy holding my cock more and more as I looked at the illustration. Then all of a sudden, white liquid came out of the end of my cock - it was the most lovely thing.

Of course, I had long since known about wanking. Sharing a bed with two older brothers meant it was impossible to avoid. I would lay in between them, sweating profusely and trying to sleep amid intense shaking from either side of me.

Pat had already told me how babies were made when I was seven and he was 13 (I told the other kids at school, but none of them believed me). Now I was delighted. Perhaps Pat, Joe and I would do it together. I couldn’t wait to tell Pat that I had arrived. I was wanking! But when I did, he just said, ‘Tsst. Well, don’t fuckin’ spunk on me.’ We were still all three sharing a bed at this point.

I was disappointed. To me, it seemed like a big step forward. ‘Why are you down on it?’ I asked Pat.

‘Wanking is a negative thing to do,’ he said. That puzzled me, because he’d been very enthusiastic about it when he was 13 or 14. He went on to say that instead of going out and achieving things, some people just lived in fantasy, and wanked. That made sense, and I felt a little bad about my new hobby, but it didn’t affect the frequency with which I did it.

I did mention that I recognise my own face in Rowland’s reflection. Here we go.

I had, by this time, lost trust in my own perception. I made my decisions based on what I thought were other people’s values (Dad’s, mainly, but also other members of the family, as well as outsiders). If I was asked a question, I would have to think about who was asking it and what answer they would want to hear, or what answer would get me the least stressful outcome. It was confusing. And bloody hard work. I had become an over-thinker - inevitable in those circumstances. Looking back, I see that I felt there was no way out. My situation was internal. I was defective. That feeling would increase in intensity in the years that followed.

My father and I had a very contentious relationship until his brain tumours got blasted and/or he just changed. After that, I felt he was, well, not exactly relatable, but we did connect. It got better until my father died. I hated my father a lot during my first couple of decades, and I loved him, but then I just loved him. Surface-level, Rowland seems to have had the same kind of relationship with his father, which seems to have coloured a lot of his relationships.

It’s pretty clear that some of us sons who didn’t get praise sung by our dads ended up looking for acknowledgement and camaraderie in a lot of dodgy ways and places, no wonder.

There’s a lot of soul-searching in the book. One thing I love about Rowland’s story-telling is how he paints a picture in the book without using adjectives, just tells the story. Here’s an example.

I started to have second thoughts about getting married and recalled previously hearing Dad saying that when a young unmarried girl got pregnant it wasn’t always best for the couple to get married, as it could ruin three lives. His point of view surprised me at the time. But in any event, I had started to think differently. I was 20; Sophia was 19.

After a few days, I said to Sophia, ‘Please, babe, have an abortion.

I’m not ready for a child now. Maybe if we’re still together, we could think about it again at some time in the future.’ I was trying to pull out all the stops.

God, and my daughter, please forgive me for wanting to have my child aborted. I didn’t think of it in terms of a human life. At this time, I saw children as nothing but a nuisance. The idea that having a child could be something enriching was an alien concept to me.

Sophia agreed to end the pregnancy and said she and her mum would look into it. Apparently, though, there was a problem with the waiting list. Then her mum told me that, although Sophia was still planning to have the abortion, they had also booked a bed at the hospital to have the baby, just in case.

After a while, it became clear that Sophia was going to have the baby.

[..]

I explained to them that in 1982 when Dexys did well and I started to earn some money, I phoned Billy and asked him if he could track Sophia down. This he did. Billy learned that when my daughter was four years old, Sophia took up with a good man. They stayed together and married.

I also explained that after Billy had found the address in Scotland, I wrote to Sophia and offered money to help with whatever was needed for my daughter. She would have been eight at that time. Sophia and her husband wrote back saying they didn’t want help, that my name wasn’t on the birth certificate, and should I contact them again, they would engage a solicitor.

I love how Rowland writes about loving music. Here’s his recollection of hearing Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks:

I’d never heard music that went this deep or made so much sense of the way I felt. I related to the pain being expressed. I didn’t know it could be expressed with such beauty. That was a revelation, and this was great art.

Van’s music was deadly serious, and that was exactly how I felt. Ever since I could remember, people had always been telling me to cheer up.

But this music, for the first time, validated the way I felt, and much more.

I couldn’t understand why anyone would not see this as the best thing they’d ever heard. For example, ‘Caravan’ on It’s Too Late to Stop Now. […]

Those lyrics didn’t even make a whole lot of sense to me, but it didn’t matter, because on a much deeper level I totally understood it, in a way that I can’t even explain.

Dexys didn’t just make one masterpiece; I think they did it with Too-Rye-Ay and Don’t Stand Me Down. Mind, Rowland did this after most of the band left him after they’d released and had a world-famous hit with ‘Come On Eileen’. He rebuilt everything, wrote soulful lyrics, music, and devised a new visual style for the band. What? Who does this? A fucking visionary artist, that’s who.

I have a lot of heart for Rowland because of how he’s owned up to faults and confesses them, plainly, in sight for the world to see. For me, this sounds very close to the Alcoholics Anonymous twelve-step programme, where one of the steps requires you to own up to what you’ve done and ask for the forgiveness of people you’ve slighted.

There is one very important point that I need to make: I didn’t steal one note, one melody, one chord sequence or lyric from Kevin Archer’s music! Not one. All of the music was written by me, Jim and one or two others in the band. What I did steal was the sound and style of the music, mainly on ‘Celtic Soul Brothers’, and also the idea of breaking down and speeding up, which I used on ‘Come on Eileen’.

What I did was wrong, and Kevin Archer deserved much better.

Furthermore, we would not have had the success we did without Kevin’s input. There is no question about that.

Also, some years later, in 1988, and well after the success of ‘Come on Eileen’ and Too Rye Ay, I did something equally mean-spirited. Kevin’s band finally did release a single, which used something akin to his original sound. On being asked what I thought about it in a music paper interview, I replied: ‘Oh, it’s just Dexys, isn’t it.’

That was really cheap. Here was an opportunity to maybe go some way to making an amend and possibly help Kevin’s band along a little.

I couldn’t even do that. Very sad. Kevin, now, rightly receives a significant percentage of the songwriting royalties from ‘Come on Eileen’ and the Too Rye Ay project, and has done for many years.

Then there’s the addiction.

I thought being well known would make me more confident. The opposite happened. You can’t switch fame off. The only alternative is to stay in. And from the end of that touring cycle, that’s pretty much what I did.

Ecstasy and cocaine came along. Millions of English pounds were squandered and stolen and abused.

I was living only for cocaine. My budget was, of course, severely limited. Sometimes, I would spend all my dole money on cocaine and in the following days I’d be trying to find pennies around the flat to get myself some fish fingers or pasta. Sometimes, I couldn’t find anything.

‘Cocaine is a different drug the way you do it,’ a dealer friend had said to me.

He was right. I did it in big fat lines, then just sat or lay there for five minutes or more, in silence, with my eyes closed, drifting off into peace.

My relationship with it was more like the way people use heroin.

In my early cocaine days, I liked to chat with people, hang out and have fun. Now I just wanted solo oblivion. I didn’t want to talk to anyone. Initially, cocaine gave me energy. Now it made me feel tired, but still with an overactive brain.

I became much more paranoid and totally believed any negative comments or thoughts about myself. Those thoughts had always been there, but now had much more power. If I was out socially (and that was becoming rare), I’d be talking to someone and simultaneously there would be another powerful dialogue going on in my mind. I’d be thinking, I wonder if this person knows I’m a no-talent fake.

The honesty about doing drugs is not the thing here. Of course there are tales of fun, ruin, death, and music. But the key bits and lovely thing that Rowland does is, as mentioned, laying it all out here.

I had heard someone in the meetings saying, ‘When you can’t stop, pray for the willingness to stop.’ I did that. I got down on my knees and begged. Nothing changed for a few weeks. Then right out of the blue, on a day that was by no means the worst, a very strong feeling came over me: I just can’t do this any more. I can’t live like this any more.

I knew there was a meeting the next day at noon. It was a question of hanging on till then. I counted the minutes and hours until, finally, I was so happy to arrive at the meeting.

They had a section reserved for newcomers. I said, ‘I’m back and this time I’m staying. Day one!’ I meant it.

They gave newcomers a white plastic chip, which signifies surrender, and that’s what I was happily doing admitting I was beaten. That was 28 August 1993.

Everything could have ended here, but it doesn’t. Rowland goes on in life, rebuilds everything: gets a flat, earns money to pay his mountains of debt, gets in contact with his biological daughter, starts making music again, plays live. And he releases My Beauty, a truly amazing collection of songs by other people; the tracks were arranged and sung by Rowland. Look to see if you can find more beautiful versions of ‘The Greatest Love of All’ or ‘Concrete and Clay’, I dare you.

There’s much beauty to see in the eyes of the hurt who have caused hurt.

On My Beauty.

People were saying I was crazy. Maybe I was, I thought. It seems incredible now that wearing a dress could evoke such vitriol and, even worse, the most patronising ‘well-meaning, caring’ attitude towards this guy who was so vulnerable, he had lost his marbles’. It was such bullshit.

And there were so many double standards going on. For example, I did an interview with Billy Bragg when he was guesting as the host on a Radio 2 Saturday afternoon show. During the live interview, Billy picked up the album cover. Laughing, he pointed to the picture and, in his broadest Essex accent, sneered, ‘Look! You can practically see your cream crackers there, mate.’

That old feeling of shame engulfed me. The blood went up to my head. I was overwhelmed and unable to defend myself.

He had turned all blokey. It was only later, when I could compose myself, that I realised the absurdity of somebody who presents themselves as politically ‘right on’ demonstrating such double standards. If he’d picked up a picture of a woman and made the same comments ‘Look, I can practically see your minge there, babe’ - he would rightly be lambasted. And he himself would probably lambast other men for doing the same thing.

But it was open season on me. And what he was saying wasn’t out of the ordinary.

The fucking courage of a middle-aged man to stand on an album cover in drag, not for show, but for beauty.

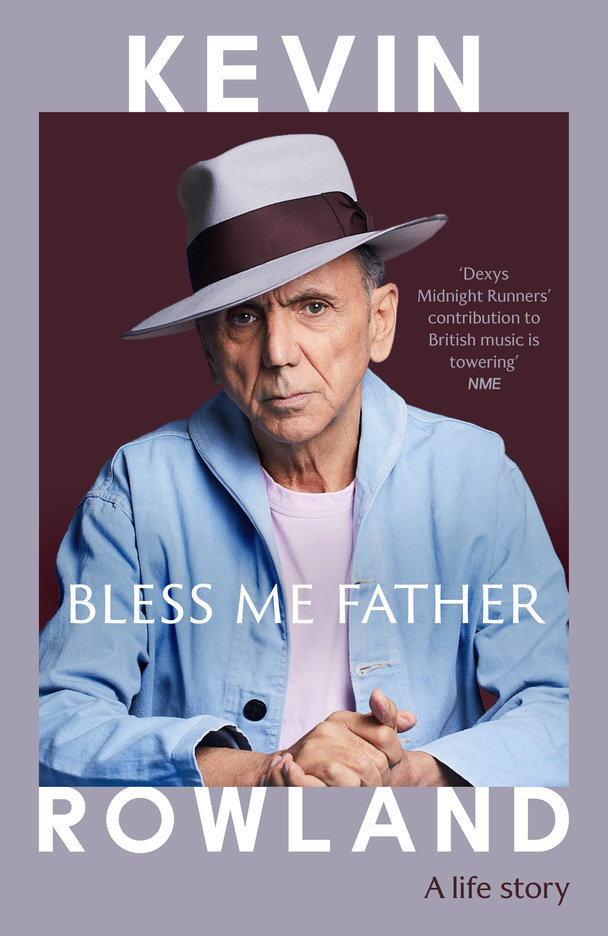

This book is probably going to be the memoir of the year for me. His publicity people say Rowland will likely not have another book published, but I truly hope he will. He’s got more in him to put onto pages. I know he has more music coming, that’s for sure. And the man is still going! Look at the remastered 2022 version of Too-Rye-Ay where Rowland finally got it to sound the way it was first intended, not to mention the latest couple of Dexys albums that came out in the past decade, along with a live album.

I applaud Kevin Rowland. He deserves praise, recognition, and love. And you deserve to listen to his soulful, fun, relatable, danceable, and radiant music, so get out there and buy some of it.

“Too-Rye-Ay.” Wikipedia, August 30, 2025. Accessed September 19, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Too-Rye-Ay&oldid=1308572808. ↩

Rowland, Kevin. “Reminisce, Pt. 1.” Music lyrics. Last modified September 19, 2025. https://genius.com/19634587. ↩